Before Congress went on recess, Rep. Graves and Sen. Cassidy, both of Louisiana, introduced identical bills in the House and the Senate nicknamed the RED SNAPPER Act of 2017 – a coy acronym for the bills’ significantly lengthier full name: Regionally Empowered Decision-making for Snapper, Noting the Angling Public and the Preservation of an Exceptional Resource Act (H.R. 3588).

The bills propose extending states’ power to regulate the recreational red snapper fishery out to 25 miles or 25 fathoms, whichever is greater, while leaving commercial and charter-for-hire regulations as they are, in the hands of the federal government past the 9 mile mark.

One reason the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Marine Fish Service (NMFS) were established was to eliminate the need for exactly what is being proposed by Rep. Graves and others. The aim of the bill is to manage a single species, red snapper, for a single sector, the private recreational anglers – a group that has a long track record of significantly exceeding their catch limits.

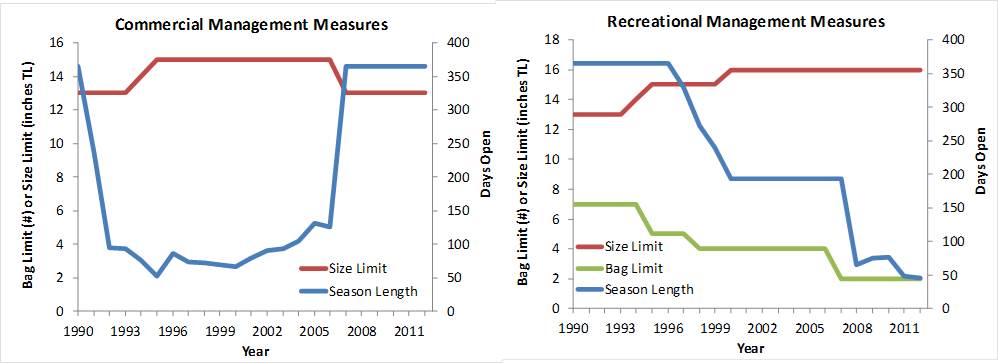

The current red snapper fishery management system developed due to severe overfishing that threatened everyone’s ability to enjoy red snapper. The 1990s saw incredibly low catches of the popular fish, numbers so low that some feared the species may not recover. Careful planning and conservation have allowed the species to rebound – though there are still years left on their rebuilding plan. This new legislation could diminish any progress that has been made thus far.

Especially in the past few years, recreational fishermen lament that their short seasons are unfair. While it’s true that three, six or even ten days seasons are unusually short for a fish that was historically readily available, two main factors have contributed to changing seasons. First, as the number of snapper increase, more fish will be caught in a given time frame. If the stock is to continue to grow, the number of fishing days necessarily reduces. Second, shorter federal seasons are in part a reaction to state regulators expanding the fishing season in state waters. In order to stay true to the rebuilding plan even as more fish are being caught in state waters, the federal season needs to be shorter. Everyone is catching from the same stock, so it doesn’t matter where the additional snapper are being caught, just that they are being caught. Recreational fishermen regularly exceed their mandated catch limits and the fishery is set up to deal with this. The response to these overages is removing the amount of the overage from the next years season – so when year after year more fish are caught than should be, the seasons get shorter and shorter.

One important determination a stock’s healthy is the average age of the stock. Red snapper do not reach peak sexual maturity for upwards of a decade, which has contributed to the long timeframe allowed for their rebuilding.

Most red snapper harvested is two to six years old and has spawned a few times, if any. This causes a problem when we are removing fish before they are given the chance to help restore the stock.

The age and size of female red snapper determines how many eggs they produce. Small females may produce as few as 1,000 eggs, with larger females capable of producing upwards of 2.5 million eggs. The relationship between age and spawning potential is not linear. In the first few years females start spawning, the number of eggs they produce can double, so by allowing females to get a few years older, the spawning potential increases disproportionately.

If fish are removed before they have had time to reproduce, the stock is at risk of crashing again. NOAA wants to let the stock reach 26% spawning potential, meaning the stock would be producing about one quarter (well 26%) of the eggs that would be produced by an unfished population. The stock is making real progress, and in 2013, spawning potential was about 24%.

According to NOAA, red snapper are not yet ready for more intense fishing efforts as, before this summer’s events, the rebuilding plan still has about six years left. This summer the Department of Commerce granted a 39-day open season, without scientific consensus or public comment, for what should have been 3 days of fishing. While the exact impacts on the fishery have not yet been determined, scientists speculate that the rebuilding plan may need an additional six years of rebuilding.

Without the RED SNAPPER Act of 2017, the commercial and recreational sectors have their own catch limits, with the commercial sector receiving 51% of the total catch, and recreational receiving 49%. The recreational share is further divided between charter-for-hire boats and private recreational fishermen, those with boats big enough to take out to depths red snapper live.

The proposed regulatory changes would only affect the latter group. Each state having the authority to determine its own open season makes the potential for abuse a real threat. If individual states leave their waters open even after their pre-determined limits have been reached, this could foreshadow a repeat of the 1990s for the fishery.

All of this is moot unless the law goes into effect. It is uncertain how likely the bill is to be passed. While it does have bipartisan support, a similar bill was introduced in 2016 by Rep. Graves that aimed to accomplish similar objectives, but it did not make it to a floor vote.

We will continue to update you as more information emerges from the Gulf.

Hannah Leis is GRN’s Fisheries Associate.