The Houston Ship Channel, a bustling waterway that stretches 52 miles from Houston’s East to the Gulf of Mexico, has long been a hot spot for industry, particularly petrochemical plants and refineries. Beyond the towering chemical complexes, just beneath the ground, lies a troubling history of racial injustice and ever-increasing industrial pollution. In fact, the Houston Ship Channel carries a dark legacy of environmental racism that began after the abolition of slavery and the subsequent implementation of Jim Crow laws and racist housing policies.

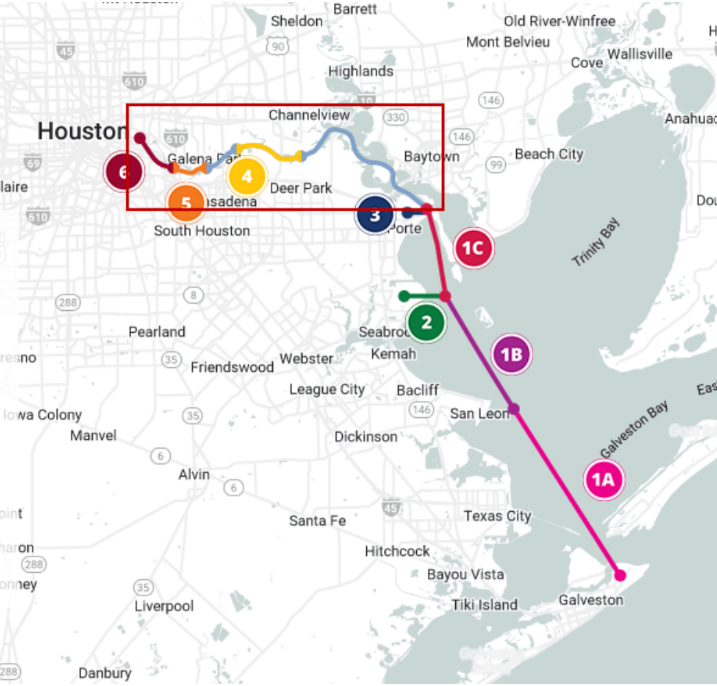

The Houston Ship Channel was originally constructed in the early 20th century as an inland port after the Hurricane of 1900 destroyed the Port of Galveston. Today, it is one of the busiest ports in the United States, but the channel’s development came at significant cost to the environment and local communities. The Houston Ship Channel began as a dredged bayou and has been deepened and widened 10 times over the decades. The Houston Ship Channel is widened by digging out sediment at the bottom of the bayou, and this material becomes known as dredge spoil.

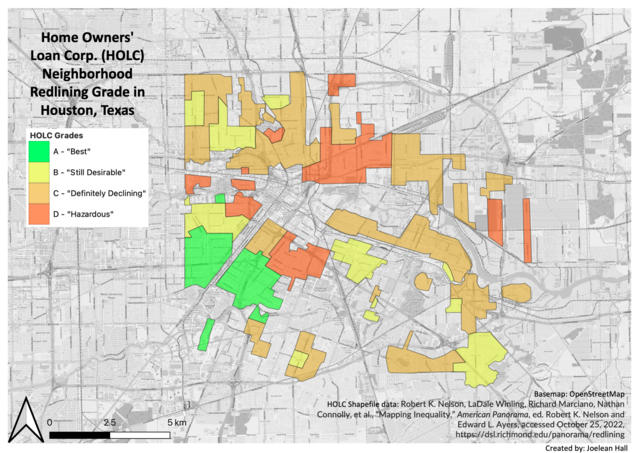

The dredge spoil from the Houston Ship Channel over the years was placed in containment areas, many of which are located in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. The dredge spoil pulled from the Houston Ship Channel is saturated with industrial pollutants from the area’s many chemical and industrial facilities. The burden of this toxic pollution is disproportionately felt by Houston’s communities of color. Subsequently, these communities are at a higher risk of health problems, including cancer, respiratory diseases, and reproductive issues. Many neighborhoods along the Houston Ship Channel are now considered toxic hotspots due to the concentration of chemical facilities and dredge spoil containment sites.

Meanwhile, yet another expansion of the Houston Ship Channel looms. This expansion, called Project 11, has been in the works for over a decade, and will deepen and widen the channel in various places, including in the inland reaches of Houston proper. Project 11, despite having an Environmental Impact Statement and decades of calls for testing and protections from surrounding communities, fails to mitigate the harmful effects of dumping dredge spoil onto the piles that loom ever higher above communities like Galena Park, Pleasantville, and Clinton Park. Residents who live near the dump sites continue to call on the Army Corps and the Port of Houston to test the existing spoil already piled in their communities for contaminants before adding more, but officials have said it is not in their protocols to do so. Furthermore, community members are calling for rigorous testing for toxins harmful to human health from the ship channel sediment that will become dredge spoil, to go beyond a cursory testing completed for the Environmental Impact Statement.

Unfortunately, the dredge spoil containment sites are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the industrial pollution with which Houston residents must contend. But Project 11 sets the tone: the expansion of the Houston Ship Channel must go forward as it is the only way to facilitate the Port’s ongoing industrial growth. It is already the seventh-largest port in the world, doing more than $170 billion in trade annually, according to Port officials.

The history of racial and socioeconomic injustices associated with industrial pollution along the Houston Ship Channel is a stark reminder of the legacy that contributes to ongoing challenges faced by Black, brown, and poor communities. The fight for environmental justice continues in these communities. As Project 11 and other initiatives move forward, it is crucial that the lessons of the past inform the decisions made in the present and future. Only by addressing the historical disparities, stopping pollution from occurring, and addressing legacy pollution, can we hope to create a more equitable and sustainable future for all.